The great refugee fraud in Cameroon

You could not get a visa from a Western chancery after several attempts. You had taken the road or the sea in the hope of entering your dream country without success. No need to panic. It is now possible to travel from Cameroon with a refugee identity.

You could not get a visa from a Western chancery after several attempts. You had taken the road or the sea in the hope of entering your dream country without success. No need to panic. It is now possible to travel from Cameroon with a refugee identity.

December 23, 2022, 9 a.m. A dozen people take part in the burial ceremony of Sepamio Sylver at the morgue of a hospital in the economic capital of Cameroon. The body of the Central African refugee is dressed in a black suit, a white shirt and a black bow tie. His friends and acquaintances, all in tears, knew that Sylver was living in precarious conditions. But they are so upset because the 31-year-old didn’t die of an illness or accident. He took his own life after a long wait to be resettled in a developed country.

In the small crowd saying goodbye to the deceased was Christophe, a man who knows how to turn the dream of traveling abroad into reality. Christophe is a member of a gang that discreetly recruits people of all ages, issues them travel documents reserved for refugees in exchange for large sums of money, and even finds them a decent job in a country in Europe, North America or Oceania.

While this practice violates the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees’ (UNHCR) guidelines for resettlement services, an employee of the local UNHCR branch is said to be the mastermind of this gang, which also includes elements of the Cameroonian police and facilitators in the Ministry of External Relations, as a reporter for the online publication The Museba Project discovered during an undercover investigation over several years.

The Cameroonian reporter posed as an individual looking for a travel opportunity. The gang told him that he would pay the sum of 2,500,000 FCFA ($4000) for all services: change of nationality, choice of host country, issuance of a refugee card, blue passport, visa and offer of employment in Bratislava, the capital of Slovakia in Eastern Europe, the reporter’s final destination. The gang first attributed Congolese nationality to the reporter before mentioning the Central African Republic because Central African Republic refugees are more likely to enter the West since their country is still unstable, according to the gang.

The journalist was not alone in his adventure. He crossed paths with another Cameroonian citizen who had changed his name and nationality, and whom the gang was preparing to send to Canada. The reporter also spoke to fake refugees already settled in the West after using the same network.

Many real refugees who should be benefiting from the free resettlement service are waiting desperately. Meanwhile, the gang is making up to 10 million CFA francs ($16,000) per family per trip, to the point that one of its members proudly declared:

“80 per cent of my income comes from this network”.

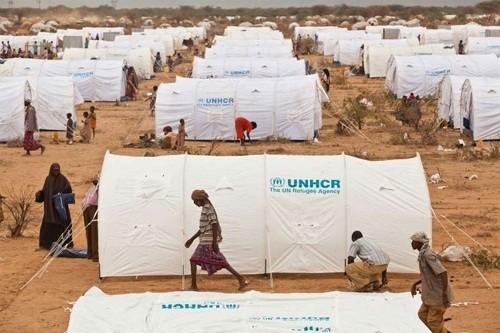

The UNHCR was founded in 1950 to provide humanitarian assistance to European refugees from World War II. In July 1951, a convention relating to the status of refugees was adopted by the General Assembly in order to seal this decision. However, this convention proved to be limited because it did not take into account the emergence of new refugee groups around the world.

In 1967, nations came back to the table with a protocol to the convention, giving UNHCR the responsibility of promoting the two international agreements on refugee protection and ensuring their implementation by signatories. Since then, 148 countries around the world have come to share a common definition of a refugee:

“Any person who owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality; and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.”

UNHCR saves lives and protects refugees, according to its guiding principles. However, when voluntary repatriation and local integration of the refugee in the country of asylum is not possible, UNHCR applies for resettlement of the refugee in a third country that can guarantee safety.

Hamma Hamadou is a former Nigerian diplomat who worked from 1996 to 2001 in Brussels where he maintained relations with UN organizations. He believes that special attention should be given to people who have difficulties because of their origin, race, sexual orientation, etc.

“These people need special attention,” he says.

“These people need decent protection from all states within their means and in relation to the UN system,” said Hamadou. “Humanity should be one community.”

The resettlement programme is not for everyone. Those concerned must first be recognized as refugees by the UNHCR, according to the UN agency, which says it gives priority to resettling “particularly vulnerable” refugees.

Suicide

Sepamio Sylver hoped at all times to be called by the UNHCR. Time was passing, he was getting older and did not have a job. He and his father, Augustin Torote, lived in a house built of planks in a crowded neighborhood of Douala. Getting enough to eat, paying the rent, or taking care of themselves were daily challenges for both men. Despite this, young Sylver did not give up. He started borrowing money to buy jewelry, rechargeable lamps and phone accessories that he would later sell on the sly, says his father.

Sepamio Sylver hoped at all times to be called by the UNHCR. Time was passing, he was getting older and did not have a job. He and his father, Augustin Torote, lived in a house built of planks in a crowded neighborhood of Douala. Getting enough to eat, paying the rent, or taking care of themselves were daily challenges for both men. Despite this, young Sylver did not give up. He started borrowing money to buy jewelry, rechargeable lamps and phone accessories that he would later sell on the sly, says his father.

Sylver looked worried, though. When I asked him if he owed anyone anything, he said, ‘Dad, it’s too late, you forgive me,'” says Torote. The young man had just said his last words. On Sunday, December 11, 2022, Sylver hanged himself in the family home. Torote had just lost one of his six children. He later learned that Sylver owed his supplier 900,000 Fcfa ($1450).

After the funeral ceremony at the Nylon Hospital in Douala, the young refugee was buried in the Central African Republic. Torote said goodbye to his son at the border, as his status did not allow him to return to his native country.

I met Torote two days after Sylver’s suicide. During our conversation, he breaks down in tears many times and confesses that this tragedy would not have happened if UNHCR had resettled him and his children in another country.

“I beg UNHCR’s forgiveness to take a look at me and the other children who are still alive so that we can try to get out of here,” says Torote, wiping his face with a black T-shirt. “Let them put us among the people who are going to leave for any country, we are going to fight there. To lose a 31-year-old child and still stay here, when I turn around I see his image, it doesn’t feel good.”

The Museba Project went through a UNHCR Cameroon briefing note from May 2014. The document provides details on refugee resettlement, which is expected to take place in seven stages. When UNHCR submits a case for travel, we learn, the resettlement country conducts its own investigation of the refugee. If the refugee is approved, the resettlement country conducts a medical and security check.

“The resettlement country, not UNHCR, makes the final decision,” the document says, noting that vulnerability does not guarantee resettlement.

“The identification of a refugee as particularly vulnerable does not necessarily mean that the refugee is eligible for resettlement or even in need of resettlement,” the UNHCR Cameroon briefing note says. Clearly, UNHCR is now using its discretionary power to select refugees for resettlement.

The UNHCR representative in Cameroon was contacted during this investigation. He declined to respond to questions from The Museba Project about the steps, third-country quotas and fraud involved in resettling refugees.

Torote Sepamio Augustin, 59, was a cab driver in Bangui, the capital of the Central African Republic. One of his brothers was an army lieutenant. Every morning, Torote enjoyed taking his brother’s children to school. In 2005, he was stopped by gendarmes sent, he says, by a nephew of François Bozizé, president of the Central African Republic at the time.

“They said I know where the lieutenant went because we are related,” said Torote, who told the gendarmes he knew nothing about his brother’s escape. He was taken to the research brigade to be heard, but things did not go as the gendarmes had planned.

“There was a gendarme of the same ethnicity as me; he understood that this case is not good. At 11 p.m., he called me and said: I’m going to give you some money and then I’m going to ask you to go and buy something for me, don’t come back. That’s how I got away,” recalls Torote, who then passed through Berberati to enter Garoua Boulai in Cameroon. He says he found his military brother in the UNHCR offices in Douala who had fled the Central African Republic.

“We met in the office, we hugged and I started to cry,” Torote says. He says his brother was resettled in France and a certain Manga, a UNHCR employee, asked him to wait his turn. “For me, Manga said your case will be settled; every time I go to see him, he tells me it’s in progress,” Torote adds.

Two people with the same identity

While the Central African refugee was waiting to be called by UNHCR for resettlement, he learned that an individual with his full name had been resettled in the United States.

It all begins on a cloudy morning in February 2015. Torote has just woken up. He is worried because he is going through a difficult time. The refugee remembers that he had done good services to a friend of his who has been living in the United States of America for a while. He decided to ask him for financial help.

“Here in Cameroon, he was a technician like me. He went to the United States. He used to help me. From time to time, he would send me 30,000 FCFA ($48) or 20,000 FCFA ($32). He would send the pictures. He said that one should always pray.

After a moment of exchange, the friend agreed once again to make a money transfer to Torote. The refugee is excited. He is already thinking about how to use his future small fortune and does not suspect anything.

However, his friend has just received some bad news. The transfer company told him that an individual with the same name, Augustin Torote, was already living in the United States. How can the same person be in the United States and Cameroon at the same time? He was able to unravel the mystery when he later met the individual living in the United States.

“He actually met this individual and found out that he was looking at a different person,” says the refugee. Torote concludes that his identity had been sold to someone else, and immediately directs his suspicions to Manga, the UNHCR employee with whom he had spoken about his resettlement.

“When he (the friend) told me about this, I told him it was Manga’s manipulations,” Torote says. “He was the one who managed all the files, who sent people abroad.

With this move, Torote had lost not only the money that would have allowed him to solve his specific problems, but also his identity, which reduced his chances of being resettled in the United States.

But the case went further. The refugees sent a letter to Antonio Guterres, who was the UN High Commissioner for Refugees at the time, to denounce the sale of the refugees’ identities. The Swiss police have opened an investigation into the case of Augustin Torote.

“A white man and a lady called me; they said they were from the Geneva police,” Torote recalls. “They asked me what I plan to do. I said that everything God does is good; it’s up to them over there to see if they can repatriate the person who changed his name”.

But this proposal was dismissed by the Swiss police, says Torote.

Several years after the incident, Torote, still reeling from the death of his son, says Cameroonians have a habit of traveling with refugee documents.

“We found 15 Cameroonian Muslims in a trip that took place recently,” the refugee says. “We changed the system. We changed the system. Now, when you arrive there is a committee that welcomes you. They ask you in a dialect the name of your village in CAR. If you stutter, they put you aside. This is how we found fifteen Cameroonians”.

Before the scandal over his identity broke, Torote was already a member of the Douala Refugee Communities Collective (CCRD), an association that brought together about 10,000 urban refugees of various nationalities. The role of the collective was to bring its grievances to the UNHCR and its partners and to defend the interests of its members. Within a short period of time, CCRD identified other cases of refugee identity fraud.

The Museba Project obtained a copy of the CCRD’s letter to the UNHCR Inspector General in Switzerland. In it, Kalema Ngongo Jean Louis, the CCRD’s president, recounts the misadventures of Kussu Bienvenu, a refugee from the Democratic Republic of Congo, DRC.

Kussu was a candidate for resettlement to Canada. He passed the pre-travel medical exams, according to the letter. But he was later told by UNHCR that he would not be able to travel because he did not meet the criteria of the host country, Kalema said. Kussu, who was a doctor by training, decided to travel with his family on his own, according to the CCRD president.

Upon arrival in Canada, Kussu learned from Canadian immigration officials that “a family (had been) resettled in their place by UNHCR Cameroon officials,” Kalema said, “…with the same identities as him and his three children. Despite several attempts, The Museba Project has been unable to contact Kussu Bienvenu to learn more.

The Museba Project also sought comment from the UNHCR in Ottawa, Canada and Washington, D.C., but neither responded to our questions.

The fraud ring’s choice of Canada and the United States to resettle the fake refugees is not insignificant. These two countries host the largest number of resettled refugees in the world, ahead of Europe and the Nordic countries, according to the UNHCR’s website. U.S. President Joe Biden has promised to resettle up to 125,000 new refugees in the United States by 2022.

In Cameroon, many people dream of moving to the West in hopes of improving their often deplorable living conditions. Some of them, discouraged by repeated failures to obtain visas, give up after a few attempts. Others, more reckless, often end their adventure at the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea, a marine cemetery that swallows up hundreds of human beings every year. When an opportunity to enter the West legally, such as the fraud ring, presents itself, those interested are willing to pay large sums of money to make their dream come true.

The CCRD president said he has repeatedly caught Cameroonians in possession of refugee documents preparing to travel to the West. Kalema said in a letter that the sums of money requested from nationals to travel as refugees vary between 3 million CFA ($4900) and 10 million CFA ($16,000) depending on the size of the family. He then began to raise his voice.

“We demand that an international mission be sent to Cameroon to investigate the resettlement of all refugees from Cameroon from 2003 to 2015 to the USA, Canada, Australia, Scandinavian countries…”, wrote Kalema. The CCRD sent its complaints to local authorities, to the UNHCR Inspector General’s office in Geneva and even to Antonio Guterres, the current UN Secretary General, at the time the UN High Commissioner for Refugees. But nothing has changed, says the CCRD.

Kalema insisted that “the facts are real and the fraudulent network of resettlement of nationals at the expense of refugees does exist here in Cameroon.

How the fraud works

As the cries of refugees became louder through documents and their testimonies, I wanted to know if the identities of refugees continue to be sold to nationals in Cameroon. If so, how does this vast refugee fraud work, who benefits from it, and why should we care?

From my observation and the testimonies of victims, the lucrative trade in refugee identities almost always begins at the same end: a UNHCR employee discovers a loophole in the refugee resettlement system. With the help of willing colleagues, he sets up a network to recruit people who want to travel to the West as refugees. Since he must avoid showing his face, this employee passes the information to a trusted refugee who is responsible for contacting interested people.

The employee then completes the instructions by telling the refugee canvasser the fees to be paid per applicant, the percentage of commissions, the time required to process the application and, if possible, the network’s hidden supporters in the local government.

In turn, the refugee teams up with one or more other refugees. The goal is to cover a lot of ground while avoiding flight, the network’s worst adversary. Once all the precautions have been taken, the team starts the recruitment process, which usually ends with good news: the resettlement of a fake refugee in Europe, Australia, the United States or Canada.

“We have the real refugees who are going to face a difficulty because the fake refugees are going to make fraudulent use of the procedures and mechanisms,” said Hamadou.

“In fact, the main risk is that it will put a doubt in the minds of the countries that host these refugees and that are in contact with the High Commission for Refugees,” he added.

Since the story about the sale of the refugees’ identities is a matter of public interest, the only way I could form my own opinion about what is really going on was to infiltrate the fraud network as an immigration applicant. On the way to the truth, I had to financially motivate the network to explain how the fraud machine works.

I submitted some personal documents to the network. My profession was written on my national identity card and I already had an ordinary passport. But the network did not pay attention to these details, perhaps because many local journalists also seek to escape the precariousness in which they find themselves.

The decision to conduct an immersion investigation was not enough to get to the heart of the network. I needed to find a refugee who had a firm grasp of the situation. Through a long-time source, I met Jean François Missengui, a Congolese refugee in his fifties. He had just given up his job as secretary general of the CCRD because, he said, he had discovered that refugees were being severely abused, including the sale of their identities.

“It’s criminal what’s happening to refugees, I’m going to denounce these individuals,” Jean François told me at our first meeting. With this fraud, it is possible for a terrorist to easily enter the West”.

Jean François admits to me that he does not know the people who make up the network. However, he agrees to team up with me to find the refugees who work for the network. This was the first objective to reach before hoping to go further. One day, while we were thinking about the strategy, Jean François told me, in a deep voice, the story of his flight from Congo, his native country.

December 1998. Jean François was living in Brazzaville when the war broke out between the Congolese army and the “Ninja” rebels of Pastor Ntumi. Jean François, who comes from the same department as Ntumi, is suspected of being a Ninja. He is being hunted by Congolese security forces. He is repeatedly intimidated and threatened.

“I couldn’t take it anymore,” says Jean François. “I decided to flee north to Ouesso on the border with Cameroon.

But the flight was short-lived. Jean François was stopped on the way by the troops of an army colonel.

“This colonel told me that, according to his information, Cameroon and the Democratic Republic of Congo were rear bases used by the Ninjas to attack the Congo, and he refused to let me pass,” Jean François said. He says his identity card was taken away from him, so he was forced to pay money to get a pass and continue his journey.

In February 1999, Jean François entered Cameroon through Socambo, a village in the eastern region near the border. He met other Congolese citizens who were fleeing. On March 20 of the same year, Jean François arrived in Douala on a bus. A year later, he applied to the UNHCR for asylum.

As soon as he arrived, the Congolese was already making news. In 2001, he was the leader of a group of refugees who wrote to the Secretary General of the United Nations. The letter denounced the bad treatment of certain UNHCR staff towards refugees, such as contempt, opacity and fraud. A UNHCR legal adviser was dispatched to meet with the group of disgruntled refugees. He promises to take their grievances to his superiors and then says:

“When you write, be careful because some people have lost their lives because of the pen, in any case, a copy of your letter is sent to the authorities in your country of origin,” Jean François recalls.

This sentence has an effect. Some refugees gave up the project of denunciation. Jean François, however, was not discouraged. He later became the secretary of the CCRD.

In December 2018, he receives a phone call from the UNHCR asking him to enroll for resettlement in the United States. He and his wife go through the preliminary interviews. Since then, Jean Francois has neither been resettled nor been informed of any rejection of his case, he says.

“I want to see these refugees, who have lost everything, who have fled conflict and reckoning, rebuild their lives with dignity,” Jean Francois tells me when I asked him what motivates his fight against fraud.

“I am sensitive to this. That’s why I took my courage in both hands to denounce these bad practices.

My first contact with the network is made one evening in Douala. Jean François and I met Christophe, a Central African refugee (the one who had witnessed the burial of Sepamio Sylver).

“When you called, I was afraid that maybe an investigation was starting,” Christophe said with a bold smile, putting his finger on his light-colored glasses, “Since I am a human rights defender, the network is afraid that I will turn the evidence I have against them.

A few days earlier, Christophe, in his forties, had learned on the phone that I was a potential candidate for the trip. He hurried to come in person to explain to me how it works.

“What you need to know is that it’s the refugee network; it’s a staff member of the legal department at UNHCR who is the head of this network,” says Christophe, who adds that this staff member doesn’t want to make himself known. “UNHCR is an international organization and the slightest leak is your career, your family at stake.

“So these staff have built relationships with some refugees who do the business. When the visa arrives and they see that the refugee (beneficiary) cannot travel or is not ready, they sell the visa,” says Christophe.

This Central African refugee tells me that the network has managed to get three Cameroonians to travel to the United States by selling the refugees’ visas. But these Cameroonians were stopped on American soil, he says.

“When they arrived, the Central African ambassador welcomed them and took them to the embassy, but when he spoke to them in Sango (the national language of the Central African Republic), no one responded,” Christophe said. “That’s how he realized that we had given the visa to foreigners.

Resettlement takes place in seven stages, according to the UNHCR. When the refugee’s case is submitted, the authorities in the resettlement country interview the refugee and make an assessment of the case. The decision is given to the refugee by the same authorities. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) organizes the medical examination of the refugee after a security check. Then, the IOM or the resettlement country organizes a cultural orientation and the trip.

The network spares its applicants this lengthy process.

Christophe says this failure has caused the network to change its strategy. For the first time since our conversation began, he mentions the name of the UNHCR staff in question.” He’s in the legal department, Mr. Ateba; he works with a team for that. “Christophe says he works for Adele, a Yaoundé-based refugee born to a Congolese father and a Central African mother. Christophe says Adele in turn works for Jean Paul Ateba on duty at UNHCR.

“This staff member told our sister (Adele) that if you have money, we will give them a visa with a guarantee from a humanitarian association that will take care of you for a month,” the refugee said. Christophe tells me that he is in charge of convincing people who want to travel as refugees to settle in the West. Then he puts the candidate in contact with Adele and his mission ends there, he says. The network, he said, asks each candidate to pay the sum of 1,500,000 FCFA ($2400).

“The good news is that to sign up you pay half of that amount and when you are given all your travel documents, you pay the rest of the money,” Christophe says. He says that Ateba is not alone in this. When the candidate pays, the refugee says, he distributes the money to colleagues who help him in the operation.

“The first payment of 750,000 CFA francs ($1,200) that he takes is to share with his relations who help him: you are involved here, here is your share, etc. He gives everyone his share. He gives everyone his share.

Christophe shows me official documents of Cameroonian nationals who have recently traveled as Central African refugees to Canada, the United States, Norway, Spain and France. He then states that a candidate can travel with his or her name when it is similar to a Central African name. But when the name refers to certain localities in Cameroon, the network has the applicant draw up a certificate of Central African nationality and then assigns a surname that refers to the Central African Republic and the resettlement process can begin, Christophe says.

In both cases, the candidate obtains a refugee card and a blue passport (the one for refugees) with a visa. “It’s a very closed network, it’s beyond even my comprehension; I play my role as an intermediary and I stop there, I don’t even want to know how things are going over there,” says Christophe. I take his phone number and promise to contact him later.

Adele, the hub of the gang

Christophe’s last words still make me want to discover this “very closed network”. I understand that he has given me all the information he has and I decide not to contact him anymore. Jean François and I manage to get Adele’s phone number from other refugees. As a bonus, Adele speaks Lingala, Jean François’ mother tongue. On the phone, on several occasions, Adele is inexhaustible when she talks about the network and its advantages. We decide to go to Yaoundé to meet Adele.

Adele is a short lady with a chocolate complexion. Seen up close, she would be in her fifties. She was dressed up and chose to receive me in a makeshift bar far from curious eyes. “It’s a safe network, you don’t have to be afraid,” Adele reassured me. “I had two of my children travel with this network, the third lives with me and will leave soon. Adèle says that the network is sponsored by Ateba. He is assisted by a certain Mvondo who also works for the UNHCR, she says.

After this welcoming speech, it was time to give the first installment of the total amount, 750,000 FCFA ($1200).

“Times are hard, if we can help young people like you to travel to fight and that we also earn something, it makes me happy,” says Adele in a soft voice.

Later, Adele shows me a picture of a young man she says is based in Turkey after traveling from Cameroon through the network. Jean François and I manage, thanks to our research, to contact another Cameroonian living in France. He claims to have been helped by Adele and her gang.

“I was afraid at the beginning but I told myself that I have nothing to lose since it is difficult in my country,” says the young man on the phone, “I gave the money to a lady, she did everything.”

A few months passed. Adele contacted me again to ask me to provide the network with some of my official documents in order to establish my blue passport. She says that the network has chosen to send me to Bratislava, the capital of Slovakia, with a bonus job. But, she says, if I don’t agree, the network will find me another country. I stood by my choice of Slovakia.

“They gave you the nationality of Congo Brazzaville but you are not going to go to the UNHCR for the formalities, they will know that you don’t have a Congolese accent”, Adele tells me. Later, Adele tells me that the network has given me a new nationality. “It’s better that you have Central African nationality. That’s what makes it easy to pass. Since the country is still at war, the whites prefer refugees from there,” says Adele.

For months, I recorded audio and video conversations with the network. Each time, Adele reports back to me on the opinions of Ateba, Mvondo, and even a certain Gladys who also works for UNHCR. The Museba Project has not been able to confirm that Mvondo and Gladys are UNHCR employees.

The network at a point changed its demands during the process. According to Adele, Ateba said I will instead pay 2,500,000 FCFA ($4,000) to get the refugee card, passport, visa and a job in Slovakia.

“If you think this amount is high, we will keep the 1,500,000 FCFA but as soon as the passport is issued, we will give it to you and you will travel at your own expense,” Adele told me. At this point, there is no turning back. I accepted the proposal.

Adele affectionately calls Mvondo “Mr. Mayor”. He is a short, round man with a light complexion. He has made a name for himself when the network has asked for a new sum of money. Addressing Jean François, Mvondo said: “If you have other people interested, you must bring them to us, you will earn something; 80 per cent of my income comes from this network.

Dieudonné or the anointing of the police

Shortly afterwards, Adèle asked me to come to Yaoundé for an appointment at the passport office. The day before the appointment, I met Adèle with a man by her side. She introduces me: “It’s the first time you’ve met? You’ll go together tomorrow to the passport department,” says Adele, turning her gaze to the man with the strong frame.

Kemayou is his Cameroonian name. But when he came into contact with the network, almost everything changed, he tells me. He has Central African nationality and a Central African name. Canada is his final destination. I had already done the passport but there was a mistake that’s why I’m going back there tomorrow,” Kemayou explains to me.

Kemayou’s presence reassures me that the network is really at work and that I can stop by to follow the evolution of his file. But first, I had to let the passport stage pass.

The next morning, Mvondo, Adèle, Jean François, Kemayou and I met in a public garden in Yaoundé. Suddenly, a man with a light complexion appeared. It was Dieudonné, a policeman. Adèle told him that Kemayou and I were the two candidates for the passport. “Mr. Ateba has already given you something, hasn’t he? So you take good care of them,” Adele tells Dieudonné. Adele says that Dieudonné is one of the members of the network within the police. She adds that the network also has “facilitators” in the Ministry of Foreign Relations.

After a moment’s discussion between Mvondo, Adèle and Dieudonné, it was decided that I would go first. Kemayou will wait.

Dieudonné and I crossed the road. At the entrance to the passport office, the policemen at the guardhouse recognized Dieudonné and let us continue. Inside, several users are sitting on long benches. The group of uniformed and plainclothes policemen were all over the place. My heart starts to beat very fast. The risk is high. The slightest false move at this stage could lead to serious problems and my cover could be blown. At one point, I wanted to leave. But when I thought of the victims of the fraud, I encouraged myself.

Dieudonné leads me to Ambassa, one of his colleagues in charge of helping the candidates to fill in the passport application forms, and then he disappears. When asked if I already had a passport, I didn’t know what to say. The network did not tell me whether to answer yes or no. Ambassa is surprised by my hesitation. “You know Dieudonné? Who is he to you,” he asks me. I answer that he is a family friend. I ask him if he can call Dieudonné. Which he does without hesitation. A few moments later, Dieudonné arrives all anxious as if he was dreading some incident. He tells me to check the “no” box.

Ateba, Mvondo, Kemayou: silence is bliss

Was Ambassa aware of the existence of the network? I don’t know. Dieudonné knew about Ateba. Adèle reminds him that he received a sum of money from Ateba to treat my case. I have repeatedly asked to meet with Ateba, but Adèle has always refused.

“Mr. Ateba will be there at the end to give you the travel documents,” she always said.

I decided to end my encounter with the network at this point. And to follow the progress of Kemayou’s case from a distance.

In Douala, Kemayou spends most of his time in his small store, which is sparsely stocked with foodstuffs. Kemayou is married and has five children. His first contact with the network goes back a few years. “One day, a good friend who knew I wanted to travel introduced me to Adele’s network. He told me that his cousin had gone through it to enter Europe. It was this friend who put me in touch with Adele,” Kemayou tells me.

The man was indeed eager to leave Cameroon. His last attempt was to go to Australia, but he could not get a visa, he says. “I had paid a lot of money to be passed off as a human rights defender attending a seminar, but in the end I was denied a visa,” he said.

Things are moving quickly with Adele. The network asked Kemayou to pay the sum of 2,500,000 CFA francs ($4,000); he has already paid half of it, he says. Kemayou tells me that he is in possession of a Central African refugee card and that he is only waiting for his passport to be issued so that he can settle in Canada with his little family.

“It’s a network that works but it’s a little slow, you just have to be patient,” says Kemayou. I ask him if he has met Ateba since he started dealing with the network. He tells me that at one point he was beginning to lose patience and as each time Adele told him that Ateba asked him to wait, he decided to go and meet Ateba to reassure himself, he says. The fake refugee went to the UNHCR office in Yaoundé without Adele’s knowledge.

“They showed me Ateba’s office. I told him that I came on behalf of Adele in relation to my file. He explained to me that it’s really not up to them. They just make a request, and until Canada gives the agreement, they can’t do anything, because when you go there, you enter the refugee center,” says Kemayou.

Kemayou says he met Mvondo in Ateba’s office during his visit. There were two tables in that room, Mr. Ateba’s and another gentleman’s. I did not know him. It was when I saw him another day with Adele that I knew that he was the one they call ‘Mr. Mayor’.

Like Mvondo and Ateba, Kemayou speaks little. But they all have two things in common with Adele: a love of easy money and a fear of being exposed. During a conversation, Adele tells me about the misadventure of some Cameroonians from the English-speaking part of the country who were recently arrested in Australia with refugee documents. Repatriated to Cameroon, they were detained along with their accomplice, a UNHCR employee who would have made them refugees.

The Museba Project contacted Jean Paul Ateba on duty at UNHCR in Yaoundé for his comments on Kemayou’s allegations and accusations of complicity in fraud. He did not respond until this investigation was published.

“If people are having fun creating this kind of traffic, they are endangering the whole process of protecting people who need real protection from the United Nations, that’s what this is about,” Hamadou said. The former diplomat added: “It is neither good for the countries from which they leave nor good for the global refugee system.

The sale of refugees’ identities is a reality. Torote, Jean François, Kalema and their families may never be resettled. But history will remember that they had the courage to speak out against a serious injustice, the courage to alert their fellow human beings. In time.

By Christian Locka (The Museba Project)

Used with permission.