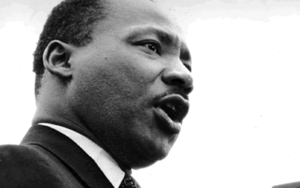

Martin Luther King Jr., women, and the possibility of growth

The fabled civil rights leader’s treatment of women bears re-examining in the #MeToo era, but King also demonstrated the capacity to grow before his life was cut short.

As much as his life is worthy of honour and celebration, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. likely would have had a hard time during the recent searching examination of gender inequities prompted by the #MeToo movement. Yet unlike some men who appear unwilling or unable to get beyond casting themselves as victims, King could well have had the ability to grow on this vital issue.

The fabled civil rights leader’s public challenges with women ranged from the structure and workings of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) he co-founded with the Rev. Ralph Abernathy and into his writings about women.

Women played a limited role in the SCLC. Here the experience of legendary organizer Ella Baker is instructive. Baker struggled to have her voice heard and her vision of a more grassroots style of organizing accepted by leaders of the male-dominated organization. This disagreement prompted Baker, who played a key role in the formation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, to counsel young members like John Lewis to retain their independence from the older group. Historian Barbara Ransby wrote in her 2003 biography of Baker that the SCLC ministers were “not ready to welcome her into the organization on an equal footing” because to do so “would be too far afield from the gender relations they were used to in the church.”

Baker’s experience of being expected to play a subordinate role in the movement was far from unique. Dorothy Height and other women also described a sexist environment. Michael Eric Dyson wrote in I May Not Get There With You: The True Martin Luther King, Jr., that sexism prevented King from forging stronger connections with “radical black women who were his great ideological allies in the struggle against economic oppression.”

Women are consistently relegated to a supporting role in King’s writings, too.

They appear as “ungrammatical,” spiritually wise elders such as Mother Pollard, a venerable figure from the Montgomery Bus Boycott. They are beautiful daughters or dedicated and loyal wives like Coretta Scott King. Sources of love, respect and even inspiration, these women nearly always exist in a constellation in which King is the central figure. Illuminating key elements of racism’s pernicious effects, they are rarely in a full and equal partnership in the struggle against white supremacy. The famous picture of the Kings walking hand in hand during the march from Selma to Montgomery is a notable exception to this general pattern.

King’s issues with women extended into his personal life.

That King was a frequent adulterer throughout much of his married life is relatively well-known. While the clash between the lofty values he espoused and his less-than-faithful behavior may be cause for critique, at the end of the day the marital understanding between King and his wife, Coretta Scott King, remained their business. Some commentators have offered the generous interpretation that his behavior was by no means unique to black ministers, especially those who were on the road as much as 250 days per year. Indeed, University of Pennsylvania professor Jonathan Zimmerman wrote in the Baltimore Sun last year that this was seen by some as an implicit reward of the position and authority it bestowed.

But physical conflict represents a crossing over the line to unacceptable behavior, no matter what the era.

King’s ally and confidant Abernathy is the source for this disturbing allegation. In his 1989 memoir, And The Walls Came Tumbling Down, Abernathy described a conflict with a woman on the last day of King’s life. King and the woman argued loudly about his dalliances with others before he “knocked her across the bed,” Abernathy wrote, adding that the two “for a moment were in a full-blown fight, with King clearly winning.”

It’s important to note both that others who were there denied that the incident happened and Abernathy faced extensive criticism from others in the movement who considered his revelation of King’s infidelity, if not the alleged violence, an act of betrayal. In a representative example, Pulitzer-prize winning columnist William Raspberry compared Abernathy to Judas and concluded his piece by writing that “Abernathy’s tales out of school didn’t diminish King; they diminished Abernathy.”

Still, Abernathy’s account is a source of concern. And taken together, these elements paint a disquieting portrait of this national icon.

And yet the picture is not quite as bleak as it might appear when one considers the capacity for growth through reflection and experience that King demonstrated throughout his career.

King did not seek out to lead the bus boycott in Montgomery, where he had lived for barely a year before Rosa Parks’ arrest. In fact, he was tapped by city elders precisely because he was new in town and did not have some of the baggage accumulated by other leaders who had been there longer.

Nevertheless, he rose when summoned by the community and the moment. He declared famously in the meeting just four days after Parks’ arrest to a crowd of nearly 5,000 people at the Holt Street Baptist Church that he and the others gathered there were not wrong: “We are not wrong in what we are doing. If we are wrong, the Supreme Court of this nation is wrong. If we are wrong, the Constitution of the United States is wrong. If we are wrong, God Almighty is wrong. If we are wrong, Jesus of Nazareth was merely a utopian dreamer that never came down to earth. If we are wrong, justice is a lie. Love has no meaning.”

But when King joined the Montgomery Improvement Association in 1955, the organization’s initial proposal called not to get rid of legalized apartheid, but for the bus drivers to act with more kindness toward the black riders. The group only issued the call for full integration after the city elders arrogantly rejected their position.

The movement’s ambition, and King’s vision, steadily expanded in the ensuing years as he worked with thousands of others to dismantle American segregation throughout the South — a decade-long push that culminated in the Voting Rights Act of 1964 and Civil Rights Act of 1965. From there, he turned to tackle economic and housing issues in Chicago. Toward the end of his life, King broke with the Johnson administration on the issue of the Vietnam War. Speaking at New York’s Riverside Church one year to the day before he was assassinated, King decried the “triplet of racism, materialism, and militarism” and called for a revolution of values. Throughout his final year of life, he continued to move and speak in an increasingly prophetic tone and voice. When he was killed, he was working to organize a Poor People’s Campaign that would unite people of all races and called for a fundamental redistribution of resources.

King showed greater moral courage over time on issues of homophobia, too.

In 1960 he bowed to threats by Harlem Congressman Adam Clayton Powell Jr. that Powell would claim that King and his close adviser, Bayard Rustin, were having an affair. Rustin was gay, but King had no sexual relationship with him. This led to a three-year exile from the movement for Rustin.

But in 1963, King and others rallied around Rustin in the face of segregationist Sen. Strom Thurmond’s denouncing him on the Senate floor as a draft-dodging communist, homosexual and a convicted “sex pervert.” Thurmond made his comments shortly before the March on Washington for which Rustin was the lead organizer.

The march went forward and Rustin read a series of demands after King delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech. King’s support for him never wavered again.

All of this augurs well for King’s ability to grow on women’s issues and raises the question of why he didn’t advance in this area during his lifetime.

The historian Lewis Baldwin, author of the book, Behind the Public Veil: The Humanness of Martin Luther King, Jr. pointed out in a 2016 CNN article that King was “far ahead of most men of his time,” citing his support for women being ordained to the ministry.

The answer, of course, remains unknowable.

But as we stop to reflect on King’s remarkable life and actions as he would have turned 90 years old, it important both not to look away from his limitations on the critical issue of gender as well as to consider his continued capacity for growth that he might well have harnessed in this area, had he lived long enough to do so.

By Jeff Kelly Lowenstein